I recently received some completely unexpected and very kind tweets about my most recent book, Call of the Northland. I say recent, but it's already six years old. Apparently, the reader bought the book last year and recently got around to reading it. The timing was uncanny. I've been thinking a lot about that book recently, but not in a good way.

Maybe I went about writing it in the wrong way. I chose to title this post the "afterlife" very deliberately. For me, publication was the end, not the beginning. I didn't think much about reception (I was just starting my MA and was a tad busy). To this day, I've never read my book in full, but I have read enough to make me cringe. In particular, I am very upset with the way I portrayed Indigenous people and Indigenous issues. My understanding at the time was beyond superficial and played into more stereotypes than I was conscious of. In all likelihood, I probably did a better job than the majority of Canadians would have in 2014, but still. I have learned so much since, nowhere near enough, but the connections between Indigenous life and infrastructure have become my 9 to 5. Most importantly, I have learned how much I don't know. If Call of the Northland were written today, it would be a very different book.

I don't want to say I'm ashamed of the book now, even though I am, and I rarely mention it to people. I suppose I should be proud. After all, were it not for Call of the Northland, I probably wouldn't be studying the relationship between Ontario Northland and Indigenous communities today. I love the work and I still love writing. I guess I'm pretty lucky.

One of the tweets asked about the sequel. It's true, another problem with a book is that it captures a moment in time. The story ends the day that it hits the printer. Someone picking up Call of the Northland in 2020 is reading my thoughts from six years ago. I did upload an "updates and corrections" document that concluded at the end of 2014, but I haven't said much since. In the past six years, Ontario Northland has gone through a sort of rejuvenation. Bus transportation has become much more prominent within the organization, as has the remanufacturing division. The Polar Bear Express has been upgraded for the first time in nearly 30 years by refurbishing the passenger cars made surplus by the cancellation of the Northlander. Of course, this move means that Ontario Northland would need to source more passenger cars if the Northlander were restarted. The fate of the Northlander itself remains uncertain. In April 2020, the Doug Ford government shifted oversight of the Ontario Northland Transportation Commission from the Ministry of Northern Development & Mines to the Ministry of Transportation. The last time that Transportation was in charge of Ontario Northland was back in the 1970s, which was an era of expansion and innovation for the railway. Don't get me wrong, I think it is far too soon to celebrate, but the signs are more positive than they were even two years ago.

I don't think that the repositioning of Ontario Northland as a transportation, rather than a development, entity is a proactive move. The transportation landscape in Northern Ontario has changed a great deal since the attempt to divest the Ontario Northland was cancelled in 2014. The CN (formerly Algoma Central) passenger service from Sault Ste. Marie to Hearst doesn't run anymore. VIA Rail reduced service on the Toronto-Vancouver run. Greyhound cancelled its bus services in the region as well. If the Ontario government had not shifted its thinking and worked with Ontario Northland to boost bus service first with the (ultimately aborted) Manitoulin Island expansion and more recently with expansion to White River, Thunder Bay, and Winnipeg, Northwestern Ontario would have been completely isolated with the exception of private cars. While some smaller bus companies tried to fill in some gaps, the region needed some sort of network. In December 2020, the Ministry of Transportation published its new strategy for Northern Ontario transportation, including a serious examination of reinstating passenger rail service between Toronto and Northeastern Ontario. Time will tell if this amounts to anything, but the signs are better than they have been for quite some time. As I said, this change of direction is not so much proactive as a reaction to a rapidly changing transportation situation. In particular, it has become impossible for government to ignore Indigenous issues, even if this attention does not always lead to better, more respectful outcomes. The Ring of Fire mining exploration continues, although plans for rail connections are now off the table. The focus is now on road development and establishing better communications infrastructure. The Ford government has also loosened environmental assessment requirements, which has upset many Indigenous communities (see my point above about better, more respectful outcomes).

So, what's the story since 2014? It's one of a leaner Ontario Northland setting off in different directions in Ontario and beyond with, at least for now, better government backing. COVID-19 has changed transportation everywhere, so these are still uncertain times. All in all, the attempted divestment from 2012-14 is beginning to fade into the background. It had lasting effects, but they were perhaps not as drastic as had been predicted. In Call of the Northland, I predicted that I would never see the North again. It was a bit dramatic perhaps, and in the summer of 2019 I did visit North Bay, travelling by bus from Toronto. I have to say it: Ontario Northland buses are comfortable with decent leg room. No, they don't beat the train, but things could be much, much worse.

If there is a lesson here, it's that books have a life - or an afterlife as I like to think about it. They are a snapshot; a moment in time. Sometimes they sit on a shelf and gather dust. But sometimes, they jump out again.

Monday, December 14, 2020

The Afterlife of a Book

Wednesday, April 08, 2020

Why Pierre Berton Should Not Define Canadian Railway History

During the past two weeks I have been filling one of those reading gaps that shouldn’t exist. If you claim to study some aspect of railway history in Canada, you really need to know what Pierre Berton said in his two-part chronicle of the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway: The National Dream and The Last Spike. After all, Canada’s unofficial historian probably penned the most-read account of anything rail-related in Canada.

My reluctance to read his work was because I thought I knew what he would say: the construction of the CPR built Canada, it was a triumph over untamed wilderness, it was the heroic endeavour of a bunch of white guys. Oh Berton, I misjudged you. A little.

Don’t get me wrong, that’s basically what his two books say, and he tells it like the master wordsmith he is. But that isn’t the whole story here. I tried to approach these books from the perspective of an Indigenous history of the railway. I had assumed that Berton had nothing to say about Indigenous people and the railway. I assumed wrong. Indigenous people are present in several parts of the books. But I think that actually makes it worse. Berton actually has some very emotive passages about the impact that the CPR had on Indigenous people, but his grappling with this issue is even more clumsy than mine is.

Even before the construction of the railway really gets going, we catch glimpses of the tropes that Berton uses. Surveyors “tended to fall in love with the virgin territory they explored.” (Berton, The National Dream, 156) Here he plays with two notions: the myth of wilderness, and the penetrative (sexual) conquest that so informed the colonial mindset. This is a land (and everything in it) for the taking. Were it not for acknowledging the legacy of the HBC, you would think the CPR had stumbled across terra nullius.

It’s in the The Last Spike, however, that Berton really gets going and his thoughts on Indigenous people are worth quoting at length:

But then Berton changes tack and things get a little disturbing. Berton tries to explain the benevolence of government agricultural policy, which

Things become even more messy with the Métis, as Berton spends little time going into detail about Riel’s cause, yet dedicates dozens of pages to the heroic journey of the soldiers travelling westward to suppress him. This choice does two things: firstly, it centres the Red River Resistance as a settler issue and, secondly, it makes Métis and Indigenous resistance a sideshow to the imposition of law and order by the Canadian state. This denies Indigenous agency. More broadly, this sidelining suggests that First Nations and Métis people are not part of the Canadian historical narrative, a position apparently only held by settlers. As most writers have, Berton also indicts Poundmaker, although this assertion has now been thoroughly discredited. As Berton explains, the defeat of Riel marks the end of Indigenous resistance and I find this claim to be rather amusing. If resistance had truly ended, would there still be First Nations and Métis people across the Prairies today?

Pierre Berton undoubtedly did much to further the Canadian understanding of its past, but he did so within the confines of his time. I suggest that he knew more than he said, and that in doing so he perpetuated the stereotypes and quiet acceptance of colonial government policy that still hurt Canada today. In a related vein, the Onderdonk's Chinese workers in the Rockies are described in detail, albeit largely in terms related to government policy. This also reinforces the notion of Canada as a nation of immigrants, which further erases the Indigenous presence.

As Andy den Otter lamented in the late 1990s, Berton's narrative of the CPR has been taken as gospel by both the Canadian public and Canadian historians. While The Philosophy of Railways did a lot to counter Berton's understanding of what motivated railway construction, it did not address the complex issues of the Indigenous perspective. Since den Otter's book was published, only one monograph has dealt with Canadian railway history. But rather than further our understanding of the Indigenous perspective, Saje Mathieu's North of the Color Line shows us that we understand railway history even less than we thought by investigating the transnational networks of African-American and African-Canadian sleeping car porters. So, do we really know Canada's railway history at all?

My reluctance to read his work was because I thought I knew what he would say: the construction of the CPR built Canada, it was a triumph over untamed wilderness, it was the heroic endeavour of a bunch of white guys. Oh Berton, I misjudged you. A little.

Don’t get me wrong, that’s basically what his two books say, and he tells it like the master wordsmith he is. But that isn’t the whole story here. I tried to approach these books from the perspective of an Indigenous history of the railway. I had assumed that Berton had nothing to say about Indigenous people and the railway. I assumed wrong. Indigenous people are present in several parts of the books. But I think that actually makes it worse. Berton actually has some very emotive passages about the impact that the CPR had on Indigenous people, but his grappling with this issue is even more clumsy than mine is.

Even before the construction of the railway really gets going, we catch glimpses of the tropes that Berton uses. Surveyors “tended to fall in love with the virgin territory they explored.” (Berton, The National Dream, 156) Here he plays with two notions: the myth of wilderness, and the penetrative (sexual) conquest that so informed the colonial mindset. This is a land (and everything in it) for the taking. Were it not for acknowledging the legacy of the HBC, you would think the CPR had stumbled across terra nullius.

It’s in the The Last Spike, however, that Berton really gets going and his thoughts on Indigenous people are worth quoting at length:

“To the Indians, the railway symbolized the end of a golden age – an age in which the native peoples, liberated by the white man’s horses and the white man’s weapons, had galloped at will across their untrammelled domain, where the game seemed unlimited and the zest of the hunt gave life a tang and purpose. This truly idyllic existence came to an end with the suddenness of a thunderstorm just as the railway, like a glittering spear, was thrust through the ancient hunting grounds of the Blackfoot and the Cree … From a proud and fearless nomad, rich in culture and tradition, he became a pathetic, half starved creature, confined to the semi-prisons of the new reserves and totally dependent on government relief for his existence.” (Berton, The Last Spike, 232)Let’s unpack this. Berton is clearly aware of Indigenous people and he understands quite a bit about settler contact. But he is also totally oblivious to the reality as he wrote in the 1970s, a moment when these supposedly dead cultures were growing and taking on the federal government and Canadian society. He has bought into the idea of the Indigenous being only in the past, something relegated to history that no longer concerns present-day Canadians. This is the noble savage, the passing of a stoic race. Even more, it seems that Indigenous people should be thankful. After all, their freedom had only been secured through settler horses and weapons. Both of these things had significant impacts on Indigenous cultures, but to suggest that they are what made Indigenous peoples successful is settler conceit in the extreme. Berton goes on, to the annoyance of any academic historian, stating that “The buffalo, on which the entire Indian economy and culture depended, were actually gone before the coming of the railway; but the order of their passing is immaterial.” (Berton, The Last Spike, 232) Actually, the order is very much material. If we are going to pretend it isn’t, then we are contributing to the erasure of the past.

But then Berton changes tack and things get a little disturbing. Berton tries to explain the benevolence of government agricultural policy, which

“born of expediency, was a two-stage one. The starving Indians would be fed at public expense for a period which, it was hoped, would be temporary. Over a longer period, the Indian Department would attempt to bring about a sociological change that normally occupied centuries. It would try to turn a race of hunters into a community of peasants. It would settle the Indians on reserves, provide them with tools and seed, and attempt to persuade them to give up the old life and become self-sufficient as farmers and husbandmen. The reserves would be situated on land considered best suited for agriculture, all of it north of the line of the railway, far from the hunting grounds. Thus the CPR became the visible symbol of the Indian’s tragedy.” (Berton, The Last Spike, 232-33).Berton didn’t have Daschuk’s Clearing the Plains to read, but he seemed to have a lot of information at hand. So, why didn’t he say that the starvation was in fact part of the government policy of coercion? Would not transforming a “race” into a “community” against its will be tantamount to genocide? Were reserves really placed on prime agricultural land? (Actually, Daschuk says sort-of, although hobbled by government policy and inadequate resources). In Berton's retelling, the government is taking on a tough sociological puzzle; what brave visionaries! This painfully romantic image of the situation (which we can look back on, tut-tut at our forefathers, and move forward from) is sugar-coated in a way which makes me suspect that Berton knew more than he said. When he suspects he has said too much, he re-centres the story: the Indian Commissioner Dewdney and the CPR are cold of the plight befalling Indigenous people until Father Albert Lacombe intervenes to save his Indigenous followers. Once again, the story becomes a settler-dominated one.

Things become even more messy with the Métis, as Berton spends little time going into detail about Riel’s cause, yet dedicates dozens of pages to the heroic journey of the soldiers travelling westward to suppress him. This choice does two things: firstly, it centres the Red River Resistance as a settler issue and, secondly, it makes Métis and Indigenous resistance a sideshow to the imposition of law and order by the Canadian state. This denies Indigenous agency. More broadly, this sidelining suggests that First Nations and Métis people are not part of the Canadian historical narrative, a position apparently only held by settlers. As most writers have, Berton also indicts Poundmaker, although this assertion has now been thoroughly discredited. As Berton explains, the defeat of Riel marks the end of Indigenous resistance and I find this claim to be rather amusing. If resistance had truly ended, would there still be First Nations and Métis people across the Prairies today?

Pierre Berton undoubtedly did much to further the Canadian understanding of its past, but he did so within the confines of his time. I suggest that he knew more than he said, and that in doing so he perpetuated the stereotypes and quiet acceptance of colonial government policy that still hurt Canada today. In a related vein, the Onderdonk's Chinese workers in the Rockies are described in detail, albeit largely in terms related to government policy. This also reinforces the notion of Canada as a nation of immigrants, which further erases the Indigenous presence.

As Andy den Otter lamented in the late 1990s, Berton's narrative of the CPR has been taken as gospel by both the Canadian public and Canadian historians. While The Philosophy of Railways did a lot to counter Berton's understanding of what motivated railway construction, it did not address the complex issues of the Indigenous perspective. Since den Otter's book was published, only one monograph has dealt with Canadian railway history. But rather than further our understanding of the Indigenous perspective, Saje Mathieu's North of the Color Line shows us that we understand railway history even less than we thought by investigating the transnational networks of African-American and African-Canadian sleeping car porters. So, do we really know Canada's railway history at all?

Saturday, February 15, 2020

My research interests are front-page news and I have so much to think about!

Canada is having a woke railway moment

What a moment Canadians find themselves in. A courageous movement of people have paralyzed a large portion of the national railway infrastructure and have caused what is frankly the most significant railway disruption in Canadian history. I study railway development in Northern Ontario and its impact on Indigenous communities. In short, I am in academic overdrive.

However, as my brain fires on all cylinders, I am left with far more questions than answers. I do not really study Indigenous activism, so on this side of the issue I am much less clear. When it comes to the railway, I am on stable ground. What follows is a selection of my thoughts, some of which are more complete than others. I think that all Canadians have a lot to think about right now. For many, once the blockades are lifted this will soon fade into memory, but this will stay with me longer.

What Happened?

For years, the Wet’suwet’en have been fighting to ensure that pipeline construction projects are conducted on their own terms. This happened, sort of. Elected band council chiefs mostly agreed to allow the Coastal GasLink pipeline plan to go ahead. But the elected chiefs are only representatives in the highly artificial and imposed structure of Indian Act Crown-Indigenous relations. Hereditary Chiefs, because the Wet’suwet’en are a people who have hereditary Chiefs, do not agree to allow pipeline development. This means that there is an internal conflict within their communities, let alone the tension with outside forces. For an excellent primer on this, see the First Peoples Law guide.

Many Wet’suwet’en people do not want the pipeline, so they set up camps to block construction access. Naturally, the pipeline consortium called the police, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s involvement over the past two years has made things much worse. According to the Guardian, the RCMP authorized snipers to use whatever force was needed to subdue the occupation. For those of you unfamiliar with the RCMP, it borders on paramilitary – from its tactics to its ranking system. But that was a year ago. The catalyst for this series of protests was the RCMP decision to enforce an injunction to clear the Wet’suwet’en protest camps this month. This is what caused sympathy protests to take place across Canada, many choosing to target railway tracks.

Unprecedented disruption

Unless I am very much mistaken, shutting almost the entirety of VIA Rail (except Northern Manitoba and Sudbury-White River) along with pretty much all of the eastern portion of CN’s network, is the most significant disruption to Canada’s railway network ever. Labour disputes rarely shut down every train and normally there is a wind-down period first when trains are moved to yards. This time, trains are stuck on the main line. Passenger trains never reached their destinations. I think that CN’s decision to shut down is a practical response to the situation, but I am also sure that it is partly a pressure tactic to scare the government into action. From an Indigenous perspective, these blockades are a very visible form of resistance and a real statement against the colonial structure that continues to shape Canada. After all, the railway plays a central role in the history of Canadian colonialism. For examples, see Adele Perry’s amazing Twitter thread here or my discussion of Treaty 9 in Northern Ontario here.

The most significant blockade is at a location known as CN Marysville, east of Belleville, Ontario. I was actually there last summer, just watching the trains roll by. It is a very unassuming location, but it borders the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory. If the boundaries on Google Maps are to be believed, the crossing is not actually on reserve land, but it is certainly on the traditional territory of the Tyendinaga community. This is CN’s main line between Toronto and Montreal and it carries all VIA passenger trains from Toronto to Montreal and Ottawa. Trains stopped moving on February 6, and haven’t moved since. Other blockades have sprung up across the country, disrupting railway operations in BC, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Quebec (and probably elsewhere, this is a fast-moving story). The majority of these blockades have targeted CN tracks, but CP has also experienced disruptions, notably in Southern BC. While CN has received a provincial court injunction to clear the blockade at Marysville, the Ontario Provincial Police has yet to carry it out.

The hesitancy about clearing the blockade says many things. For one, it says that the place of railways in Canada is not what it once was. By allowing the blockade to stand, the pipeline development is being given the higher priority. While the national railway network was 19th-century Canada’s megaproject, the 20th and 21st centuries belong to pipelines. While many, including federal Conservative leader Andrew Scheer, are calling on the Justin Trudeau to step in, the reality is that Ottawa can’t do much. The injunction was provincial and therefore it is up to Doug Ford’s government to act. I am not surprised that the government is hesitating. The state has learned a lot since Oka, Ipperwash, and Caledonia. While the police default is still to prepare for an all-out war, the last thing Ontario or Canada wants is violence being broadcast by the world’s media, which is perhaps why the media are having such a hard time covering this.

More broadly, we are seeing a very different tactic. While Andrew Scheer calls for Indigenous people to “check their privilege” and essentially go back to being subjugated, Trudeau is letting the protest run its course. Meanwhile, Doug Ford isn’t doing much, which he is highly skilled at doing. If Scheer was Prime Minister, the blockades would be down and I suspect blood would have been shed by now. I’m not letting Trudeau off the hook here, the Crown-Indigenous relationship remains highly adversarial on his watch and the state continues to meddle unnecessarily in Indigenous lives, but at least he likes to talk rather than lead with his fists.

Railways matter, my work matters

One of the most difficult parts of doctoral study is feeling that you are accomplishing nothing. You spend years on things that most people will think are a waste of time. For the past week, my research topics have been front-page news in Canada. I study railway development. I study how this development affected Indigenous people. True, my work looks at Northern Ontario, but this is a region that never gets any media attention. In a sense, this makes understanding the role of the railway near James Bay even more pressing. The Tyendinaga defenders of Indigenous rights chose their location wisely. It is near enough for Toronto journalists to actually visit. No doubt this will fade from media attention and I will feel my work doesn’t matter more often than I think it does, but it is also hard not to think that something is happening right now. Settler people are connecting railways to colonialism in a way that few of us have before. This is exciting.

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

Six Months On: Reflections on “Railroads in Native America”

Thirty Thousand Feet Above the Fields

One of the most striking examples of the imposition of European Enlightenment rationality onto North America is the overlaying of the grid system onto land by European settlers. The surveying of towns and farm plots for private ownership during the 19th century was a tangible articulation of the new order being imposed by settler colonialism onto Indigenous land. Flying over the American Midwest, the rigid grid structure of Iowa farmers’ fields was a striking reminder of the historical process of settlement, and its lasting form. As the plane began its descent over the Missouri River, we neared Omaha, where I would be exploring another facet of this settler colonial process: the railroad.

Throughout 2019, commemorations and celebrations were held to mark the 150th anniversary of the completion of the American transcontinental railroad. In 1869, the Central Pacific and Union Pacific met near Promontory, Utah, linking the Pacific Coast to Council Bluffs, where the UP joined up with the rest of the American rail network to the Eastern Seaboard. As Richard White has pointed out, this was not really a transcontinental railroad at all, but when its construction was combined with the frontier ethos, it felt like a bringing together of the disparate states of America, helping to heal the divisions of the Civil War.[1] The last spike was a momentous occasion for the relatively young nation, but for the people who had occupied the land for millennia, the railroad was a confusing, intimidating, exciting, and above all transformative newcomer. I was meeting a group of people who hoped to think beyond the commemorative celebrations and understand what the railroad has meant in Native America.

I don’t officially study the United States, and I certainly don’t study the transcontinental railroad. In fact, I have to confess that much of what I knew about it before this gathering was informed by the AMC series Hell on Wheels (ok, and White’s book). I was the only Canadian at this symposium, and I hoped to explain the similarities and differences between my work on railway development in Northern Ontario and the much larger project in the American West that had taken place over 30 years earlier. More importantly, I wanted to see how other professionals, scholars, and elders understood railway development and its impact on Indigenous people. As the headquarters of the Union Pacific, Omaha was an ideal location to hold this discussion, which was sponsored primarily by the UP, the National Parks Service, and the University of Nebraska at Omaha, which also hosted the gatherings. Omaha itself is an excellent example of the settler understanding of land. It is a sprawling city, over 140 square miles, with few buildings taller than two or three stories. This is a space where land appears unlimited and can be used inefficiently without consequences. Indigenous teachings tell us a different story, where actions have consequences and land and all it does for us must be respected. The development of the American West really was the imposition of a new worldview.

If nothing else happens in my doctoral journey, my few days in Omaha will have made it all worthwhile. It was my first foray into the academic world as a doctoral candidate, my first presentation in the United States, and there wasn’t a single bad paper or presentation during the whole event. The participants were friendly, knowledgeable and, above all enthusiastic about the topic. While the work was all of a truly excellent quality, several of these discussions really stood out for me, and it is these that I want to reflect on. (For a full list of presentations and presenters, visit the Union Pacific Museum’s website).

The California Myth

Until very recently, most people’s understanding of California’s past was the story of the Missions: Franciscan outposts spaced a day’s journey apart as Catholicism headed North along the coast. The Spanish place names all over California seemed to corroborate this Hispanic heritage. After all, who else would pick names like San Diego, San Luis Obispo, or Ventura? It turns out that it was mostly Anglo-Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. California is home to one of the most enduring historical myths in the U.S., and Indigenous history blows it apart.

As Michael Connelly Miskwish and Theresa Gregor showed, the Mission Myth is an act of historical erasure. California was home to a wide variety of Indigenous peoples, and perhaps the greatest concentration of Indigenous languages anywhere. “El Camino Real,” as we have come to know it, was really a weak patchwork of missions, mostly concentrated around Baja California. In many cases, the Padres met strong resistance, controlled little land, and most mission development was abandoned by the 1840s, but not before disease had significantly weakened Indigenous communities. The coming of the railway and later roads encouraged local businessmen to promote the region to investors. To do this, they chose to resurrect the piecemeal mission system and to bolster it through a constructed Hispanic heritage. A key tactic in constructing this was to replace Indigenous place names with Spanish ones: Tecuan became Tijuana, and so forth. By constructing the idea of “El Camino Real,” the Automobile Club of Southern California hoped to attract tourists looking for the mythical Spanish past. All this helped to hide California’s Indigenous past and marginalize the surviving tribes. Only recently has the California Genocide been acknowledged as an act of physical and cultural erasure.

But there is another, equally troubling side to this story. Historians and educators have been complicit in perpetuating the Mission Myth. Until very recently, all California 4th grade students were required to complete what is known as the “Mission Project,” a history module where a passing grade was determined by how well a student could retell and explain the Spanish Missions. For Indigenous students, who knew better, they could choose to accurately explain the erasure of their cultures and the imposition of the Spanish myth (and fail), or toe the line (and pass). As the complexity of California’s development has become more widely known, the curriculum has been revised, and the “Mission Project” now allows for multiple interpretations. Why were educators complicit? According to Miskwish and Gregor, the Mission Myth was too vital to the California tourism industry to lose.

Food Sovereignty

I don’t study food history, but Adae Romero-Briones and Hillary Renick convinced me of the railroad’s role in damaging Indigenous foodways. Railway development reshaped land, which in turn reshaped cultivation patterns and migratory routes for animals. Railroads and the farmers they brought introduced new animals to the West, like pigs and horses, which upset existing ecosystems. Railroads were part of an extractive system, where commodities like bison were collected in mass quantities and then shipped away. In fact, in the Cochiti language, the same term is used for white railway passengers and for invasive species. As the railroad promoted tourism, it built the pottery industry, which shifted Indigenous communities to a cash economy, which also changed how food was sourced. Where Indigenous people had once grown their own food, they now needed money to buy it. Perhaps most damaging, railroads brought in a sugar-heavy diet, which continues to wreak havoc on Indigenous (and frankly settler) health.

But all is not lost, as these two strong community leaders showed, the tide is turning and Indigenous communities are reclaiming their food sovereignty. Key to this is getting the next generation interested in food and in cultivating traditional food practices through local projects. Most importantly, we need to see the dollar as a tool, not the end-goal.

The Telegraph

In Canada, the telegraph was synonymous with railroad development. In the U.S., it actually predated it by eight years! And just like the railroad, one company built east and one west, with the two meeting at Salt Lake. As Edmund Russell explained, this complicates our understanding of the role of the telegraph in the colonization of space. Here, the telegraph is actually the agent driving railway development, not the other way around. While Russell is now a senior scholar, he is very much at the same juncture as me: we are both trying to take an established historiography and challenge it by thinking about how Indigenous peoples fit into the picture and about how this changes our understanding of technology. With the telegraph, it was obviously a technology foreign to tribes. It was both a dramatic demonstration of settler technology, and a dangerous system that could deliver a powerful electric shock (something that was done to unsuspecting Indigenous people on more than one occasion). But its construction also offered opportunities for guiding and supplying of the construction crews. We cannot forget, however, that the technology also encroached on Indigenous land and was met with armed resistance on multiple occasions. This resistance meant an increased army presence in the West, and the improved communication offered by telegraphy boosted military efficiency. In the context of the American West, Russell argues, we can see the telegraph as a prototype for the railway development that followed it. These ideas will be part of a larger book project on the construction of the transcontinental telegraph and I am looking forward to reading it.

The Symposium Painting

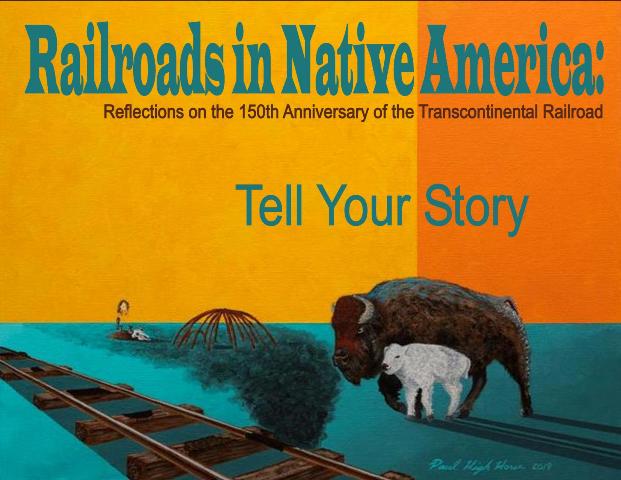

Sitting near the entrance was a modest-sized painting by Sičáŋǧu Lakota artist and teacher Paul High Horse. This is an image steeped in symbolism depicting the coming of the Ȟemáni, the Lakota word for train. The track is coming from the East, the land in the West darkens as the railroad approaches. The white buffalo, a symbol of peace, will not cross the track as a cloud of smoke follows the right-of-way. But this is but a moment in time: the smoke will disperse; and the nearby lodge and altar are still standing. In this painting, the visual representation of the symposium, the railroad is a powerful transformative force, but one that will pass just as smoke does not linger forever. The land will outlast it, and so will Indigenous peoples.

Metal Road

The short documentary, Metal Road, was something I was not expecting to see, but it was an important reminder that Indigenous interactions with railroads are not all negative. For generations in the Southwest, the Union Pacific has employed a track gang made up almost entirely of Navajo workers, often including multiple generations of the same family. Their employment came at a moment when the UP was desperate for manpower. After WWII, Mexican labourers brought in to keep the railroad operating were deported, leaving a void in UP’s workforce. Track maintenance is hard work for anyone, but it has two main advantages that have kept some Navajo coming back. Track work is outdoor work and allows for a continued connection to the land. Further, track maintenance shifts are often intensive with substantial breaks in between. In the case of the UP, shifts are either four days on/three off, or eight days on/eight off. This time flexibility allows Navajo workers to remain close to home for long periods of time and retain a great deal of autonomy.

However, it isn’t an ideal situation because this shift design wreaks havoc with seniority and benefits, and the Navajo reach retirement age with no security, something that advocates within the railroad are working to remedy going forward. This is part of a wider commitment UP is developing to better engage with tribal communities and to make their employment opportunities more attractive for Indigenous people.

Meskwaki Understanding of the Railroad

If any one paper offered a blueprint for the sort of rethinking of the railroad that I hope to do, it was Erik Gooding’s presentation of the Meskwaki perspective on the UP’s tracks through their territory. In North America, the Meskwaki is an unusual Indigenous community because it lives on private land secured with the help of the state of Iowa over 100 years ago. As a result, the railroad needed to negotiate for access to the area, promising free passage (which doesn’t mean much when passenger rail is abolished). Critical to the Meskwaki understanding of the railroad is the separation of train and track. The train is a momentary phenomenon and soon passes by. On the other hand, the track is a permanent presence and its alteration of the land is more lasting. Gooding listed the multitude of ways the railroad has influenced life, both in good and bad ways. The right-of-way changed the landscape; scared wildlife; caused environmental damage (especially through derailments); increased access to alcohol and provided an easy option for suicide; disturbed traditional land use; and cut their territory in half. But there were also more positive developments as well. The railroad provided some employment, its bridges offered an easy (but risky) route across water, and it fostered cultural contact with the hobo community so lauded in nearby Britt.

As Gooding pointed out, the key here is balance and to understand the railroad as both a positive and negative force. An anthropologist, he has worked with the Meskwaki for over 20 years and developed the presentation in collaboration with them. Recently, the railroad has completed extensive drainage upgrades on Meskwaki land without consultation. These upgrades have caused sacred gardens to flood. By presenting this problem in his paper, Gooding is bringing it to the attention of UP representatives who are responsible for Indigenous relations. This is an excellent example of the reciprocal scholarship advocated by Indigenous scholars such as Kovach and Smith as a way of conducting research in a good way.[2] In this relationship, Gooding is granted the insights necessary for his presentation and the Meskwaki’s views are conveyed to the UP through the presentation. Both sides benefit.

How the Osage Beat the Railroads

As David Treuer explains, we often talk about doom and gloom à la Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee or the presentation of the stoic Indian in Ken Burns’ and Stephen Ives’ The West, but this is a misrepresentation of the historical record.[3] The Osage are often brought forward as an exception to the rule through their royalties from oil discovered on their land, but as Alexandria Gough showed, their ability to negotiate extended to the railroad as well. Back when railroads were vying to cross the Indian Territory, the Osage were able to skillfully negotiate the legal system in Washington and prevented railroad encroachment on their land.

When a breakaway group of warriors attacked local settlers, railway and government interests used the incident as a way of forcing the Osage into abiding by the Sturges Treaty, which forced the sale of Osage land to the Leavenworth, Lawrence and Galveston Railroad on unfair terms. In an example of excellent political skill, the tribe hired a lawyer and took their case to Washington, arguing that they had been coerced into giving up their land. So compelling was the case they presented that President Grant ultimately declared the Treaty to be annulled, a decision that was upheld by the Supreme Court. The railroad remained stuck on the edge of Osage territory and ultimately went out of business. This early victory encouraged the Osage to further hone their ability to take on the American government and led to new treaties offering generous and meaningful concessions in exchange for access to land and resources. When we talk about Indigenous peoples and the development of a settler society around them, it would be inaccurate to assume that it was a straightforward victory for the growing United States. In some cases, the original inhabitants beat Americans at their own game and came out ahead.

Indigenous Capitalism?

Like the Osage, Robert Voss demonstrated how the Choctaw and Chickasaw understood that railroad development might be used to their advantage. At the time of the 1855 Net Proceeds Act, both asked for rail access, but this was denied. Voss argues that this was an attempt at Indigenous economic development and that the federal government did not want to encourage this. However, the development restrictions placed on the Indian Territory allowed tribes to tax businesses that wanted access to the resources on their land. Through this, the Choctaw became important mine owners and by the 1890s, they were even asking for the help of federal troops to act as strike breakers. Again, this paper challenges our idea that Indigenous peoples have no agency and that the government and settlers always had the upper hand.

Gerard Baker

As bizarre as it sounds, there is one direct flight from Toronto to Omaha each day. In fact, it’s the only international flight to the city. Unfortunately for me, it departs mid-afternoon, and when the symposium closing ran late, I needed to duck out before Gerard Baker could finish his closing remarks. I’m sorry to have missed the end, but grateful for what of his wisdom I was able to listen to.

Baker recounted how, in one of those rare but delightful moments when government forgets what it’s doing, he was appointed to head the commemorations for the anniversary of Lewis and Clark’s journey to the Pacific. Thanks to his leadership, the commemorations were not a celebration, but a sober reflection on what two hundred years of settlement had meant to Indigenous peoples. He encouraged us to be angry about the changes that development, including the railroad, brought. But he was clear that this anger must be used positively, to push for a greater understanding of what happened and to work towards making it better. Now is the time for settlers to listen, to learn, and then – and only then – to act. These actions must be done in collaboration with Indigenous peoples, for only through this reciprocal approach can we live in a good way.

Northern Ontario?

One thing that Gerard Baker emphasised over and over again in his closing remarks was that we must think about what the legacy of the symposium would be. I think about this every day. What did those gathered in Omaha contribute? What did I contribute? What do I do now? Although my students never seem to believe me, thinking takes time, and so my research and thinking continue slowly to move forward. I am thinking about what a railway is. As Gooding explained, do we need to separate the train from the track? All of these papers, including the wonderful ones I have not mentioned above, show how the Indigenous perspectives can no longer be ignored when we think about railway development. Most of the events discussed took place in the mid 19th century, and Canada was watching. By the time the Ontario government was building tracks through Northern Ontario, treaties in Canada were being worded in such a way as to prevent the sort of agency that the Osage and the Choctaw had demonstrated. As always seems to be the case, Canadian history is like American history, only a bit different. I keep working my way through the ideas surrounding railways, infrastructure, government power, colonialism, and Indigenous understandings of all of these things. As I do so, I am reminded of the energy in that room over those days. I am reminded of how privileged I was to be able to learn from so many people coming from so many backgrounds. I am reminded that my work, and all of our work, matters. Railways shaped North America and now it is time to really think about what that means.

1. Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011).

2. Margaret Kovach, Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009); Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Second edition (London: Zed Books, 2012).

3. David Treuer, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present (London: Corsair, 2019).

Categories:

Canada,

Conferences,

Indigenous,

Rail,

United States

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)